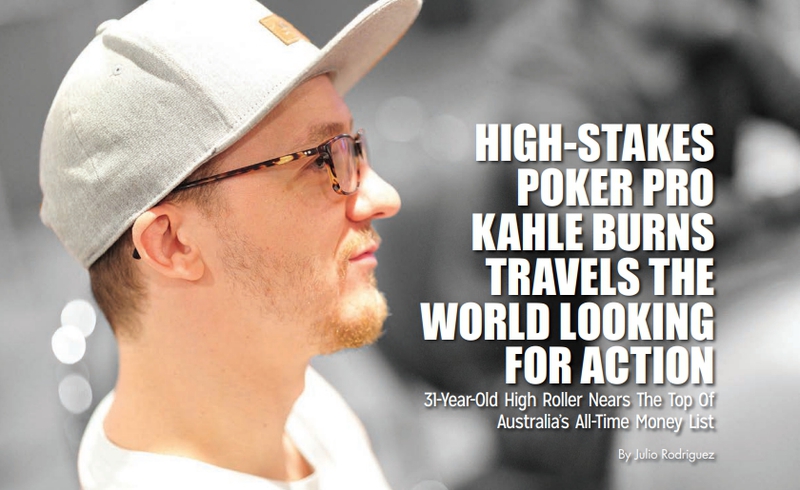

High-Stakes Poker Pro Kahle Burns Travels The World Looking For Action31-Year-Old High Roller Nears The Top Of Australia’s All-Time Money Listby Julio Rodriguez | Published: Nov 04, 2020 |

|

|

Kahle Burns just wants to play some cards.

The Australian poker pro exploded onto the live high roller scene in 2016, and has since recorded nearly $11 million in earnings, becoming one of the more dominant players on the tournament circuit.

The Geelong native started his run with a win at the nearby Sydney Championships for $226,295, and has gone on to rack up an additional 26 scores of six-figures or more since. His largest cash came in October of 2017 in the Triton Super High Roller in Macau where his third-place finish was worth $1,319,630. He pocketed another seven-figure score in January of this year when he took down the Aussie Millions AUD $100,000 high roller for $1,204,988, and followed that up with a runner-up finish at the AUD $250,000 Super High Roller Bowl Australia for another $828,000.

In addition to making his mark in the high rollers, Burns has also earned two World Series of Poker bracelets. In October of 2019 at the WSOP Europe festival, Burns won the €25,000 buy-in high roller event for his first bracelet and the $662,540 first-place prize. Just days later, he picked up his second bracelet and another $113,036 in the €2,500 short deck event.

But although it may appear that Burns came out of nowhere to join the elite high roller players, the truth is that he opted in more out of necessity than by an ego-driven need to see himself holding trophies in the winner’s circle.

More than anything, Burns just needed a game.

More than anything, Burns just needed a game.

“Live tournaments are always going to be good, just because you can’t bum hunt people, and [they draw amateurs] because people enjoy the thrill of going deep. In cash games, everyone has 100-big blind stacks and the variance is so much less, that amateurs just get fleeced so fast. In tournaments, there’s a lot more variance, and stacks are shorter to push smaller edges. But what I like about tournaments the most is that you just get your tournament ticket printed, there’s a random table assigned, and you just [sit down]. Anyone can play,” he explained.

While it makes a more dramatic story to leap from play money games to high roller events, in reality, Burns had already spent many years prior working his way up the cash game ranks, playing the biggest games he could find. In fact, Burns would travel to Las Vegas during the WSOP and only play in the main event, choosing to spend most of his trip playing nosebleed cash games at Bellagio.

However, the games started to dry up. He was simply too good to find consistent action.

“I’ve definitely played a lot more cash games than tournaments in my lifetime, and I think I probably prefer playing a big live cash game over anything else, to be honest,” Burns admitted. “But it just started becoming too hard to find games to play.”

To keep going, Burns started making trips to Macau, forcing himself to play long sessions and even living in the world’s largest gambling market for months at a time to find a good game.

“There’s not much else to do, and you have to play really long, sometimes 40- or 50-hour sessions,” Burns recalled. “I definitely used to do that for a period of time, but I don’t think it’s a super healthy lifestyle. I don’t recommend it. If I could play good, big cash games in Melbourne, Australia, I’d probably stay there most of the year, but that’s just not the case. Even if you can find one, you have to travel, and there’s politics to get in and all this other stuff to deal with.”

It’s a far cry from how the games used to be. On Card Player’s Poker Stories podcast, Burns told the story of the AUD $1.6 million pot he played with a wealthy businessman.

“I was in Melbourne, and I had heard that there was a $200-$400 game playing four-handed in Sydney,” Burns recalled. “It was just a one-hour flight, but when I got there, the game wasn’t running. But there was this guy who was supposed to play another guy heads-up for a lot of money, something like $500,000 or even a million. I was getting some mixed information from some people, [who didn’t want me in the game]. I told them I was going to ask the guy if I could play, and if he said no, I was going to leave. Instead, they offered to sell me a bit of action, but I refused. I didn’t want to buy any action, I wanted to play.”

Once again, Burns just wanted to play some cards. He eventually got his way and was able to sit down heads-up. Even better, the other players decided to invest in him!

“We started out playing $200-$400, simply because they didn’t have a bigger [placard] where we were playing. But this guy just kept wanting to jack up the stakes. We thought we were going to play $1,000-$2,000, which we did, but then he would lose [a big pot] and just point his finger up in the air. His translator would tell us, ‘He wants to go higher,’ which we already knew. He did that a couple times until I essentially had to tell him, ‘Bro, I can’t afford to go any higher. You’re going to tap us out in one hand if we keep going.’”

It was at stakes of $2,000-$4,000 that the key pot went down. Burns looked at pocket queens and decided to call on the button. His opponent raised it to $24,000, and Burns limp-raised to $80,000. The player then four-bet to $280,000. Burns made the call, noting that his opponent had about a pot-sized bet left behind. That’s when the dealer put out a rainbow flop of K-7-7.

“He thought for ten seconds and said he was all in. It was a very large portion of the money we had to play against him, but I knew I was going to call. I didn’t think he’d play aces, or A-K this way. He’d bet smaller [with those hands]. He wouldn’t need to go all in, as he would already have the hand on lockdown. I do remember thinking, ‘If I’m wrong, with all of these people who invested in me watching, they’re going to think I’m a f***ing [idiot], calling off their money with two outs.’”

Burns made the call, and hoped for the best. The dealer put out an ace on the turn, which wasn’t the most ideal card in the deck to see, especially when his opponent perked up and squeezed out his hole cards. He got some immediate relief from his buddy on the rail, however.

“My friend, who was watching and saw the cards, just said, ‘He’s got J-10, he’s dead.’ So, we held, and this guy didn’t give a f**k. He just rebought straight away.”

The games were this juicy for a while, but then they became less consistent, and the whales started to improve.

“There was this guy in Macau who was the most fun opponent,” Burns said. “When he first started playing, he was playing $1,000-$2,000, $5,000-$10,000 HKD. He didn’t know how to play at all. He was basically learning as he went. He would look at you, stare you down trying to get a read, and even go so far as to come across the table to feel your pulse on your wrist [before making a decision]. Or you’d be in the tank against him, and he’d just look at you and hold out his own wrist so you could feel his pulse. But I remember coming back after a couple months, and that guy went from playing any suited hand against a three-bet out of position, to suddenly folding overpairs. It was unbelievable how fast he had learned to play, but it shouldn’t be surprising. If he’s playing stakes that high, he is clearly successful elsewhere, and he’s probably a pretty smart individual to begin with.”

Although his opponents may have jumped head-first into the shark-infested waters of high-stakes hold’em, content to pay big for a poker education, Burns himself had a much more cautious introduction to the game.

“I sort of discovered poker just after high school. One of my friends was playing and he was doing pretty well online at $50 [buy-in] no-limit, $100 [buy-in] no-limit. He was a smart guy making decent money, and I thought maybe there was something to it.”

This occurred way after the poker boom, of course. Now 31 years old, Burns was a disinterested teenager when fellow countryman Joe Hachem won the 2005 WSOP main event for $7.5 million.

“I had seen [poker] on television, and I remember hearing when Hachem won the main event, but I was quite young at the time. I was only 16. I hadn’t really played hold’em before, so I didn’t think much about it. My parents always liked card games, like cribbage, but not poker.”

Burns started slow. Very slow.

“I was a huge nit back in the day,” he admitted. “I was scared to play for real money because I didn’t know what I was doing. I wanted to dip my toes in somewhere it couldn’t hurt me financially. So, I just started playing for play chips.”

It didn’t take long for him to master the free tables, running up a couple million in play chips. He then started to play at pub events, perhaps risking $10 at a time. After finding some strategy resources online, he finally walked into a casino and sat down at a $50 buy-in no-limit hold’em game.

“I started to win pretty much right away,” he said. “Everyone was pretty bad back then. This was 13 years ago when I was 18. C-bet (continuation bet) and be a nit was the get-it-done strategy back then.”

Almost a decade later in his career, Burns was still making adjustments.

“I did some homework on tournament theory. Prior to 2016, I hadn’t really played many tournaments at all, so I didn’t think I had any business sitting down and playing high rollers with the really good players. I would always register at the start, or very early. I was aware that my short-stack game was not as good as the best players at 20 or 30 big blinds. They were just way better than me and there was nothing I could do about it. Whereas I had played a lot more deep-stacked poker than these players, because I had been playing cash games day in and day out.”

The short-stack issues were quickly ironed out as he went deeper in these tournaments and gained experience. Before long, he was firing nearly every high roller on the circuit. To date, Burns has cashed in 17 tournaments that featured a buy-in of $25,000 or more, including five wins, three runner-up finishes, and four third-place showings. Burns doesn’t like to focus on the close calls, however.

“I’ve definitely had a few second and thirds, but I don’t really look back and say, ‘Man, that f***ing sucked that I [didn’t win].’ I don’t think about that at all to be honest. I spend zero minutes on that.”

The scores have piled up, and suddenly Burns finds himself approaching Hachem at the top of Australia’s all-time money list alongside fellow high roller wunderkind Michael Addamo. But despite the recognition he’s getting from his peers and publications such as Card Player, he still has to explain what he does to the majority of people he comes across.

“I use the Scrabble analogy,” he explained. “I ask them if they have ever played Scrabble or Words With Friends, and 90 percent of them will say yes. Then I’ll ask them if they have any friends that they are clearly better than, or who are clearly better than they are. Okay, so if you play this person, and the [better] player gets nothing but vowels or trash tiles the entire game so they can’t make good words, then the worse player is going to win. But if you play them 1,000 times, and you all get even tiles, the person with the worse vocabulary has zero chance of winning. So, the tiles are the luck element in poker, and I’m the better player.”

Burns is the better player, but once again, it’s just a matter of finding a game. He was red hot in 2019, finishing fifth in the Card Player Player of the Year race, and he was off to an incredible start in 2020 with two massive scores on his home soil. But the global pandemic caused by COVID-19 shut down the live tournament circuit, moving high rollers online and putting yet another obstacle in Burns’ path. Online poker has been illegal in Australia since 2017, forcing him to live like a nomad between poker stops.

“I haven’t been home much at all, to be honest,” Burns said. “I’ve sort of been living out of a suitcase. I’d like to spend more time in Australia, in Melbourne, but that’s just not where the tournaments are and there’s no online poker. So, what are you going to do? You got to follow the job.” ♠

Features

The Inside Straight

Strategies & Analysis