Men of Action: Jack 'Treetop' StrausA Look at a Top-Notch Hall of Famer, Raconteur and Action Junkie |

|

|

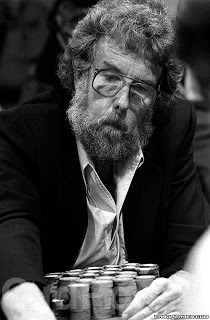

Jack Straus

We’ve all repeated it to ourselves or cringed when one of those friendly and upbeat tournament opponents cheerfully said it after watching our chips be pushed in front of another yokel.

A chip and a chair.

Maybe no poker cliché boils poker down to its purest form as “a chip and a chair.” For the downbeatens and the degenerates and the losers, the limitless potential of owning a chip and a chair is lifeblood.

It means: There’s always hope, no matter how meager the beginnings. It means: Just let me get in there to show them what I can offer. It means: Since I’ve been stripped to nothing except a single chance, there’s the potential for peace and clarity.

It’s the sixth seed winning the Super Bowl. It’s an American statement as clean and pure as the Bronx cheer or chapter one in a story that has the potential to be a classic, but will most likely end crumpled up in a wastebasket.

It’s a reprieve from the inevitable. It’s a reason to stay just a little longer.

And, in the poker world, it all started with Jack Straus, a hairy degenerate giant who turned a single chip and a chair into a World Series of Poker championship bracelet.

Straus was up and walking away from the table when someone spotted a $500 chip stuck under a napkin or a newspaper or the rail, depending on the story teller. He was just about to hit Fremont Street when they called him back to play his final chip of the 1982 WSOP main event.

A day later, surrounded by a boisterous rail running five deep, Straus would outdraw Dewey Tomko on the river to take his second and last WSOP bracelet.

And that’s where it comes from. He said it like a prayer and sometimes prayers are answered. Was he the first person to say it? Doubtful, since it seems like that phrase is one of those that always existed somewhere. But because he said it there and followed it with a run that rivals the best in WSOP history, it’s Jack Straus’s.

And he deserves it.

The Sequoia

Doyle Brunson says he was 6’7”, and old pictures show him with a bushy red beard and a curly mass of hair, so no wonder everyone called him Treetop.

Straus was born June 16, 1930 in Travis, Texas, to father Jack and mother, Mary Anderson. Little is known about his childhood or even if he was raised in Travis, a tiny town that currently has fewer than 60 people.

Other sources have reported that Straus played basketball for Texas A&M, but there is no solid evidence this happened. His name is not found in any newspaper archives between the years 1948 and 1954, nor on stat sheets from 1950.

After he graduated college, he taught for a few years before making the old Texas-Oklahoma poker circuit his life, chasing the biggest games and the biggest buzz he could find.

Straus claimed his Texas blood made him a natural card player and gambler.

“I think Texans just got a lot more guts has a lot to do with it, most other folks just don’t take the heat when you start playin’ real poker. In Texas you grow up playin’ poker, it’s a Texas game,” he told Al Reinert, who wrote an in-depth look of the role of Texas poker players at the 1973 WSOP for Texas Monthly magazine.

He made the final table in that year, as well as the year before and in 1982. Again, from the same article:

“I learned how to play from my daddy and been playin’ cards since I was six or seven, just like the rest of these Texas boys. I can remember when I was a kid they’d be shootin’ craps out in the woods. They’d lay a four-by-four piece o’ plywood on the ground and you’d get 50 or 60 cars pulled up in there, people sittin’ round drinkin’ beer and throwin’ dice. At night they’d turn the car lights on and they’d go all weekend.”

Straus’s attitude about life was simple. We are to live and play. The life of a human being is a short fuse, so why not burn as bright and vicious as possible.

“I have only a limited amount of time on this earth, and I want to live every second of it. That’s why I’m willing to play anyone in the world for any amount. It doesn’t matter who they are. Once they have a hundred or two hundred thousand dollars worth of chips in front of them, they all look the same. They all look like dragons to me, and I want to slay them,” from Bets, Bluffs, and Bad Beats by A. Alvarez.

Although based in Houston, he followed his fellow Texas road gamblers to Vegas in the 1960s, where he got the reputation as an uber-aggressive and courageous short-handed specialist, as well as a guy who needed action just as much as food and air.

Life was a true roller coaster for this giant, filled with massive windfalls of cash and just as massive losses. If he cared, he didn’t show it. A natural storyteller and a seriously freaky looking guy, he often found himself surrounded by media and railbirds at the early WSOPs and was happy to regale anyone and everyone about his philosophies.

“Jack was a good time guy, sometimes too much so, as Louise and I discovered when we went on a Caribbean gambling junket with him in Curacao, an island where gambling was legal. On the plane down there, Jack and his buddies got to passing out brownies laced with marijuana,” Brunson write in his Godfather of Poker. Louise is Brunson’s straight-as-a-knife’s edge wife.

On the way back to the States, Straus’s behavior got his whole traveling party strip-searched by customs.

Here’s how Brunson described Straus’s playing style:

“Jack was an excellent player, an action guy. In a two-or three handed game, he was dynamite. An aggressive player has an edge in a short-handed game because, if he’s got any kind of hand at all, you can’t force him out with a raise. Jack played more like I described in my book Super System than anybody I’ve ever seen.”

But the action was never too much for him and he stood in a card room with empty pockets more times than anybody can count. He lived the way-of-life that many gamblers covet. If Straus had a soul mate, it was probably fellow degenerate Stu Ungar.

From Alvarez’s The Biggest Game in Town:

“The master of this absolute, all-or-nothing way of life is Jack Straus. In 1970, a terrible run at poker in Las Vegas reduced him to his last $40. Instead of quitting, he took the $40 to the blackjack table and bet it all on a single hand. He won, and continued to bet all the money in front of him until he had turned the $40 into $500. He took the $500 back to the poker game and ran it up to $4,000, returned to the blackjack table and transformed the $4,000 into $10,000. He finally bet the whole sum on the Kansas City Chiefs in the Super Bowl and won $20,000. In less than twenty-four hours, he went from near bankruptcy to relative affluence. The story is famous enough to have gone into gambling folklore, but the real point of it is his refusal to compromise. Each time he bet, he bet all the money he had, from the first $40 to the final $10,000.”

And here’s what syndicated columnist Jim Bishop wrote about Straus in June, 1976:

“Jack Straus bet himself down to his socks choosing wrong basketball games. As he says ‘Ah got to the point wheah an couldn’t pick my own daddy out of room full of Chinamen.’”

And then, surely, everyone laughed.

Poker Breathes Life and Death

Go watch the final hand of the 1982 WSOP main event. Tomko pushes with A 4

4 , Straus goes nowhere with his A-10 offsuit. “Good Lord!” he says, when he sees what’s on the table.

, Straus goes nowhere with his A-10 offsuit. “Good Lord!” he says, when he sees what’s on the table.

His beard and curls have greyed, but he shifts like a five-year-old waiting for his birthday cake. A four comes right in the door and Straus just shakes his head and shrugs. It’s obvious — he’s used to this stuff.

Then, a ten on the river changes everything. He is shocked and his face looks like an angel just flew down from heaven, sat on his lap and left a single rose. He is in shock and happy and then finally, a big smile appears as people start to grab him and shake him, his shoulders, his hands, anything.

Then, a ten on the river changes everything. He is shocked and his face looks like an angel just flew down from heaven, sat on his lap and left a single rose. He is in shock and happy and then finally, a big smile appears as people start to grab him and shake him, his shoulders, his hands, anything.

Six years later, on Aug. 17, 1988, Straus suffered a fatal heart attack while playing poker at the Bicycle Club in Los Angeles. People like to say when something like that happens, he died doing what he loved doing, and maybe that crossed his mind when those first pains started.

He’s one of three Poker Hall of Famers to die while playing cards, joining Tom Abdo and Wild Bill Hickok.

Brunson wrote this in his book, but maybe it should be written as his epitaph:

“Jack Straus, one of poker’s great raconteurs and characters, was a piece of work.”

And the mold, as they say, was broken. ♠