One of a Kind - Stu Ungar, An insightful look into perhaps the most singular character in poker historyby Mike Sexton | Published: May 31, 2005 |

|

|

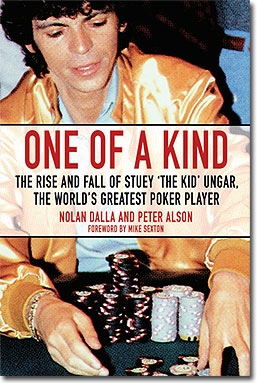

There's a new book coming out soon that I believe is a "must read" for every poker player. It's the long awaited book by Nolan Dalla and Peter Alson titled One of a Kind: The Rise and Fall of Stuey 'The Kid' Ungar, the World's Greatest Poker Player. This book is the real deal about Stu Ungar's life. I know that because I'm the one who convinced Stuey to let Nolan Dalla interview him and write the book about him (and this happened just months before he died).

Stu Ungar had the quickest mind of anyone I've ever known, and in my opinion was the greatest card player who ever walked the earth. He was far and away the best gin rummy player in history, and his legendary poker achievements speak for themselves. Yet, with all that remarkable talent, Stuey wasn't successful in the game of life, and he had every bad habit in the world.

The book is powerful. It doesn't sugarcoat anything, and it shows you the genius and the demons in Stuey's life. Many believe that he wasted his life and his incredible mind. This book provides the reader an insight into why gambling became his career with an intricate look at his childhood and life in New York.

The book is powerful. It doesn't sugarcoat anything, and it shows you the genius and the demons in Stuey's life. Many believe that he wasted his life and his incredible mind. This book provides the reader an insight into why gambling became his career with an intricate look at his childhood and life in New York.

Fellow poker player and good friend Phil "Doc" Earle was uncanny in understanding Stu Ungar and why he did the things he did. He spoke to Nolan at great length about Stuey as he was doing research for the book. Here are some of the things "Doc" Earle had to say:

"Stu was an autistic (abnormally subjective) card savant. He was not wise and learnt as a scholar, but was unconsciously brilliant and wise in mathematical odds and statistics, card sense, and reading 'vibes' from others. His memory was photographic and instant, and his mental ability to assess an overall situation and use this recall to act appropriately and creatively was done in the same instant and in parallel. He had a fraction-of-a-second brain. Before you finished explaining a card or hand problem, he cut you off and told you the answer, and if you looked like you didn't grasp it in one second, he would walk away already bored. All in one second! It was almost frightening to be with him, frightening in the sense that it made me feel that there was something eerie around and I was a part of it (which I know is true).

"Ungar had an above-genius IQ. His brain was wired differently than 99.9999 percent of the rest of us. In my opinion, it was similar to the brains of Mozart and Leonhard Euler, the 18th-century Swiss mathematician who did calculations instantly, with ease, and without apparent thought.

Stuey applied his phenomenal mental ability from an early age to what later became his expertise, and no one to my knowledge has come close to his ability in gin and to his combined abilities in backgammon, blackjack, and other card games – specifically, no-limit hold'em tournament poker.

"This early 'seeding' of his brain is what happens to the brain of gifted child chess players who go on to be brilliant chess masters like Bobby Fischer. To miss the fertile imprinting years from around age 5 to 12 is, in general, to preclude that individual from being a world class master.

"Stuey could be impatient, selfish, and volatile, yet by far this was outweighed by his compassion, kindness, trust, and generosity. He, like everyone else, had a self, and self always has contradictions, emotions, and conflicts. The background and building of that self starts as a child, at an age when imprinting is beyond our control and may, in many cases, leave a disruptive and conflicting self to handle our future.

"Ungar was unreal, and to think he would want to share his life story with you – his mystifying brilliance, accomplishments, and self-destructive tragedy – is an act of the highest unselfishness. Imagine a prince whose image to the world is that he has everything – fame,

beauty, wealth, control, and power of himself – but then confesses to the world that it is not true, knowing he will be throwing it all away! To me, that is a supreme act of truth in a moment of compassion to help others who may have the same demons as he.

"Just because a person is brilliant in some specific area (like Stuey and others in history), it does not mean that that person will be wise and well-adjusted to the 'art of living life.' This is the greatest art of all, and if you don't have it right, no matter how brilliant you are in other ways, your life will most likely be like most people's – messed up. What it takes is to 'look' in a different direction, which is mainly involved with seeing 'yourself.' I tried to talk to Stuey about this at 4 a.m. one morning in his room at the Four Queens. I got some of it across to him … and we both cried. A few of his problems were that he never learned to listen to another, talk openly about himself, or read. He never took the time.

"Stuey was an action freak – and this is a drive or a 'want' in the self that can never be appeased. Just after winning something, you are appeased, but it's an illusion. In many, this drive has its source tangled up with boredom and other personal faults that also may drive one to booze, drugs, or religious fanaticism for temporary relief. This wrong mechanism is based in the ego, the 'self,' the physiological makeup of the person.

"The most important thing I read in the few chapters Nolan sent me was that Stuey's girlfriend said that when he was around her son, Stuey was in another world – relaxed and happy! That's because he was not involved with his 'self'; he was involved with love for the child.

The self cannot solve itself. Stuey could not solve the problems of himself with his self. This is whatI tried to show him. It's so simple, but he wouldn't listen. When I asked him if he was happy, he said, "That's a good question. I don't know. If I was happy, why do I escape reality all the time?" This is heartbreaking to me, because I know why. I tried to show him, and had I succeeded, he would be alive now and still blessing us with his brilliance.

"Guys like Mike Sexton and I were fortunate to be around in the Stuey era. We saw him control (and win) tournaments like no one before or since. He would play a hand or read a person with inhuman ability, and when we watched him do it, we both turned our heads looking at each other in disbelief. He possessed skills that we would love to have as players in the game. But even after seeing him do things, and knowing it must be possible, we still had no idea as to how he did it! I mean, we're talking about Phil Earle and Mike Sexton, not exactly stupid people, but it left both of us in awe and realizing that we would never see another like him in our lifetimes.

Some naysayers stress his faults and criticize him, and that's their right, but none of the ones who do can ever say Stuey didn't honestly recognize and admit his weaknesses and faults to himself, and then share them with the world. I think the book One of a kind: The Rise and Fall of Stuey "The kid" Ungar, the World's Greatest Poker Player is one of the most interesting stories of our era. You'll see."

Thanks, "Doc," for your valuable insight into perhaps the most unique character in poker history.

I was one of three people asked to speak at Stuey's funeral (Lem Banker and Bob Stupak were the other two). The last line of my eulogy was what I wanted most. I said, "Let's forgive Stuey for his problems and faults and remember him for what he was – the greatest player to ever grace the green felt."

Take care.

Mike Sexton is the host of PartyPoker.com, a commentator on the World Poker Tour (which airs every Wednesday on the Travel Channel), and the author of WPT – Shuffle Up and Deal.

Features