Men of Action: Walter Clyde "Puggy" PearsonA Look at a Poker Legend |

|

|

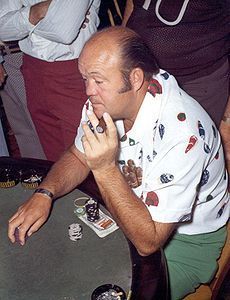

Puggy Pearson

Moss had already called an all-in bet by Pearson, assuming he’d be getting the correct odds, before a tight player they both assumed would call folded instead. Pearson knew he probably didn’t have the best hand. If the tight player called, he would’ve discarded that jack and hoped his one-card draw made him the winner.

He also knew Moss knew that he knew — all poker players know what it’s like to be on that merry-go-round of terror — but Pearson knew the math that is never all numbers.

“Well, I know what Johnny’s thinkin’ and he’s a good enough player to know that I know what he’s thinkin’, just like he knows what I’m thinkin’,” he told Jon Bradshaw for his mid-70s classic Fast Company.

“Hell, we’re environment. We know each other like the hills and the streams.”

At his best, Puggy Pearson could take all those simple numbers knowing they change depending on the environment, depending on the hills and the streams and the kind of native trout that swim in them.

Mathematicians will say numbers are absolute. Pearson would have said, “yeah, but…”

This was one of the biggest pots Pearson ever played for, and he was a little worried. But he had Moss in a bad place, and he knew it. So that’s why he stood pat with the jack. Again, from Bradshaw’s interview:

“He knows I play kinda wild. Now, he stalls and stalls. I can see the B.B.’s goin’ round and round in his head, just like he sees mine, though not so clearly — Johnny’s getting on. He also knows I’m not bluffing. I’m not. I’m playing a fine line, son. I was reading my people real good and I knew it. I was like one of those guys with a baton in front of an orchestra. I was playing it like Liberace.”

Moss “pooches” it and draws. He made a mistake, he gave Pearson the edge.

“As he draws I flop over my hand and say, ‘Johnny, you made a mistake, now beat that jack.’ ‘Oh, my God,’ he says, ‘I dumped the winning hand,’ And I raked in the pot of $62,000. Now that’s what I mean by knowin’ your human element.”

Pearson, a son of a rock crusher, knew the “environment” better than most PhDs.

Natural Born Killer

Walter Clyde “Puggy” Pearson, Jr. was born Jan. 29, 1929, in Adairville, Kentucky. He was the first son born to Walter Sr. and Gracie Pearson, the third child of nine, and didn’t go past fifth grade. In the 1930 census, his father’s job was listed as “none.”

In the 1940 census, after the family moved to Jackson County, Tenn., his father’s occupation was listed as “rock crusher” for a W.P.A. project.

Forced at 10 to get a job and help support the large brood of descendants from hardscrabble Englishmen, he did whatever a boy could find during the Depression — construction, gofer, bottle collector. His earned his nickname after showing off for some girls on a job site at a church.

A floorboard broke while he was walking on his hands and he smashed his nose flat.

A floorboard broke while he was walking on his hands and he smashed his nose flat.

At 16, Pearson joined the Navy. He missed World War II and found life in the Navy, with its monotonous days and all those nautical miles between ports, a perfect opportunity to make serious bank gambling.

He learned how to palm dice and calculate pot odds. A pool hustler and a card shark, he stayed in the Navy for three tours because, he said, the action was too good to resist. Pearson on a boat with a deck of cards and the thousands and thousands of dollars in the pockets of bored men was like an eating champion at a smorgasbord.

If he was as naturally good as hitting baseballs as he was at sizing up people, he would have been Ted Williams’ fat, slow cousin. And if Williams was good at short-changing the pot, palming dice, and angle-shooting, Williams would’ve been a Puggy.

He scooped up more than $20,000 by the time he was discharged in the early 1950s and would never work at another real job his whole life.

After the Navy, he spent about a decade based in Nashville, operating a small three-table pool hall called Pug’s and rambling around the country, playing cards, shooting pool and doing anything else he could do where he thought he had an advantage.

“He was an all-around athlete who would play pool, backgammon, golf, tennis — any game as long as he thought he had an edge. He had a great sense of his own skill, which he used to survive as a gambler,” Vegas historian and gambling analyst Larry Grossman told the Las Vegas Sun after Pearson’s death in 2006. “During the era of Johnny Moss, Doyle Brunson, Amarillo Slim Preston and Sailor Roberts — the early days of tournament poker — Puggy was as tough a player as anybody.”

Pearson moved to Vegas in the mid-1960s where he quickly fell in with the people he’d spent a decade with driving the highways from game to game, pool table to pool table. He wasn’t the first big-time card sharp to make the city’s card rooms his “office” — Moss and Roberts beat him there, to name just two — but he soon was known as one of the toughest players and prop bettors in a town full of them.

Flops, Putts, and Glory

Pearson’s gambling logic was as sound as any brokerage manager’s. Stay cool. Understand your opponent and the “environment” of the day. Know the odds. Make your opponent believe they are no good. Treat it like a business. Be fearless and trust yourself. From Bradshaw’s profile:

“It’s a funny thing — gamblin’. It’s like running a grocery store. You buy and you sell. You pay the going rate for cards and you try and sell ‘em for more than you paid. A gambler’s ace is his ability to think clearly under stress. That’s very important, because, you see, fear is the basis of all mankind. In cards, you psyche ‘em out, you shark ‘em, you put the fear of God in ‘em. That’s life. Everything’s mental in life. The butt was made to lug the mind around. The most important thing in gamblin’ is knowing the sixty-forty end of the proposition and knowing the human element. Some folks may know one of ‘em, but ain’t many know ‘em both. I believe in logic. Cut and dried. Two and two ain’t nothing in this world but four.”

A scratch golfer, he was a legend on the course and would gamble for stratospheric amounts. During his prime, he could chip and putt as well as PGA Tour members. The most he won on the golf course in one day was $300,000, according to Jack Sheehan in an article for World Golf Magazine.

He gave Sheehan some insight, saying, “you can’t be afraid to lose your entire bankroll. The way you guard against that is betting smart. You need to know you got the stone nuts before you put the peg in the ground.”

The $300,000 win was nice, but he suffered six-figure losses on the course, too. “It’s like the stock market,” he told Sheehan. “You just want more ups than downs.”

Doyle Brunson also said he had to pick anyone in the world to make a putt with his life on the line, it would be his friend Pearson.

Pearson would put in marathon card playing sessions, many going longer than 24 hours, a large stogie clenched in his puffy lips. When Bradshaw went to see him in the mid-70s, he noted how everyone seemed to know him. Waitress, casino employees, tourists, they knew who he was and had to stop and get a piece of Pearson.

“Of course they know me,” said to Bradshaw. “If you were the principal of the school, wouldn’t all the kids know you?”

Pearson’s playing style was ultra-aggressive, or “wild,” as he put it. He thought of himself as the boss. If players wanted to win, they would have to go through him. He placed himself in the doorway like a cosmic bouncer. And he filled this role for a good part of 30 years.

Pearson’s playing style was ultra-aggressive, or “wild,” as he put it. He thought of himself as the boss. If players wanted to win, they would have to go through him. He placed himself in the doorway like a cosmic bouncer. And he filled this role for a good part of 30 years.

He won four WSOP bracelets but none after 1973, when he won three of them, including the $10,000 main event. He didn’t miss a WSOP main event until his death at 77 on April 12, 2006.

One of the more enduring images relayed in the obituaries published in dozens of newspapers that week was his RV with his mantra painted on the side: “I’ll play any man from any land, in any game he can name, for any amount I can count, provided I like it.”

He was elected to the Poker Hall of Fame in 1987. ♠