Pokerstars 2005 World Championship Of Online PokerExplosive growth in just 4 yearsby Brad Willis | Published: Nov 01, 2005 |

|

|

|

Pill after pill, Mark Guttormsen topped off the bottles; 50 and sometimes 60 hours a week, the pharmacist filled prescriptions. Then, he'd go home and look at his new wife's old car in the driveway. His front lawn was barely alive and in need of some serious landscaping. It looked like – in Guttormsen's estimation – the Mojave Desert. A little money could go a long way toward making the place look a little nicer.

It had been less than a year since Guttormsen had picked up the game of poker. He played limit hold'em at first, then switched over to no-limit hold'em after a few months. When the summer months got hot, he fired up PokerStars and entered the world of online poker for the first time.

With a name like Guttormsen, one wouldn't be surprised to discover that the 33-year-old came from a line of Norwegians. As he relaxed his pill-bottle-tired fingers on the computer keyboard, his new screen name came to him.

"The Vikings were intimidating and ruthless Norwegians," he said, "much the way I play sports and poker. I play to win.

When I see blood on the felt, I go for the kill."

And so was born Viking VII.

Despite his inherent ruthlessness, his bankroll didn't support random pillaging. He had to pick his battles. Every once in a while he would splurge and enter a $50 buy-in tournament, but that was as big as his bankroll would allow.One night, he decided to pick a battle in which as little of his blood as possible could be spilled. He chose a little PokerStars Frequent Player Point qualifier for something called the World Championship of Online Poker. He won, which entitled him entry into another qualifier, which he won. The next thing he knew, he was sitting at the final table of the $1,000 buy-in event, looking at an overall prize pool of nearly $1.8 million.

"I entered the tournament with the confidence that I would do well," he said. "But, having never participated in a high-stakes tourney before, I knew the competition would be more fierce than I had ever been exposed to."

In truth, he had no idea what he was getting himself into. He would not emerge as the richest of the WCOOP participants, but he would emerge, nonetheless.Early in the morning

In Europe, the children were already in school. It was 3:42 a.m. on America's Eastern shorelines. The sun was still below the horizon, but the late-night infomercials on television made sure there was no denying the hour. It was late. Juan Valdez himself wouldn't start a final table at this hour. Guttormsen was already asleep. His WCOOP event had ended a week earlier.

The time notwithstanding, the virtual rail around the World Championship of Online Poker main event final table was full. Like the 2005 World Series of Poker final table, which stretched into Las Vegas' daylight hours, there was again a new chapter in poker history coming up with the sun.

When the final event of PokerStars' World Championship of Online Poker (WCOOP) crested the $3.5 million mark, the online gaming world felt the paradigm shift. In a matter of just 15 days, the WCOOP had done what no other online poker series had done before. It had climbed up to fight with the big boys.

Which big boys? The brick-and-mortar multimillion dollar poker tournaments. By the time the cards were in the virtual air in event No. 15, the 2005 WCOOP had generated an amazing $12,783,900 in prize money, making it not only the biggest-ever online poker event, but the third-biggest poker tournament (live or online) in all of 2005. Only the World Series of Poker and the World Poker Tour Championship had been bigger.

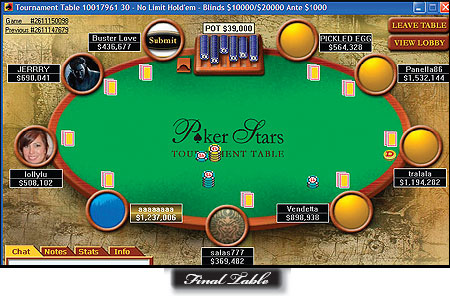

Now, the 1,494 players in the WCOOP main event, a $2,500 buy-in affair, had been whittled down to just nine. The 10th- through 18th-place finishers had all earned nearly $30,000 apiece. That in itself is a big prize for most online tournaments. Now, the final nine were about to compete for the remaining $2 million.

To be sure, this event had come a long way from where it began in 2002. That year, the entire series of nine events was worth $809,050. At the time, people thought that was a big deal. Nolan Dalla, noted poker author, said, "No one could have forecast this kind of popularity for an online poker tournament. PokerStars has proven that an online tournament can attract the same kind of turnout and prize pool as tournaments in live poker rooms."

Indeed, in 2002 it took nine events to scratch up more than $800,000 in prize money. This year, the main-event first-place finisher stood to make more than that by himself. What in the world was happening?

Four years in the making

Regular calculators aren't supposed to do anything but run the numbers. That's what they do. Don't ask them to be conservative or reckless, because they just don't understand that kind of thing. That's what computers are for. Calculators just do their jobs.

At some point in 2005, the folks at PokerStars pulled out their calculators and did the math. Math is a big deal in the world of guaranteed prize pools. Just four years earlier, when PokerStars was making its name in the poker world, the calculators spit out a number that today might get a bit of a giggle: $800,000 in guaranteed prize money over nine events. That year, the main-event winner, Sweden's MultiMarine, cashed for what seemed like a monster amount at the time: $65,450. These days, you'll see people win that amount or much more online on any given Sunday.

In 2002, then Cardroom Manager Steve Morrow had said, "The turnout for this event exceeded even our most optimistic forecasts." And perhaps that was quite true. Back then, PokerStars might not have been sure that it could scrounge up 800 grand over nine events. As it turned out, the calculators had done a fine job. The 2002 WCOOP total prize pool exceeded its guarantee of $800,000 – by $9,000.

Yes, just four years ago, only $9,000 (nine buy-ins to that year's main event) was all that separated PokerStars from digging into its pocket to make up for an overlay. And so it happened that the calculators went back to work in 2005.

This year, the calculators spit out a different number: $8 million. In just four years, the guarantee had been increased from $800,000 to $8 million. All 15 events had a guaranteed prize pool, including a $2.5 million guarantee for the $2,500 main event. PokerStars management was banking on at least 1,000 people entering the main event.

As the days and events flew by, the multimillion dollar guarantees became no more than benchmarks. In all but one event, the actual prize pools eclipsed the guarantees, generating a record overall prize pool that neared $13 million. With less than 12 hours to go before the main event, the prize pool was only half of the guarantee. By the time the cards were in the air, the guarantee lay in tatters.

"We obviously underestimated the popularity of the WCOOP events. All but one of the events dramatically oversold the guarantee," said PokerStars Poker Room Manager Lee Jones. "The inaugural $500 no-limit hold'em event, with a guarantee of $800,000, ended up with a prize pool of more than one and a half million dollars. And our $2,500 final event, with a guarantee of $2.5 million, beat that by almost 50 percent, with a prize pool of more than $3.7 million."

Who are these people?

Online screen names are a lot like vanity license plates. The numbers and letters swim together on the screen in a mélange of mystery. If you unfocus your eyes in just the right way (akin to looking at those mystery posters in shopping mall kiosks), you can figure it out. The experienced railbirds recognize the names like they'd recognize Greg Raymer (aka FossilMan) walking through the Rio. There's Gank, brsavage, neverwin, Money800, NoMercy, and Exclusive. They are the names without names, and they showed up from time to time on the WCOOP leaderboard.

But there were people who had little screen name recognition who would emerge, too. MR32 was not "Mister 32," as some people assumed, but a guy with the initials "MR" who chose the number 32, because that's how old he was when he started playing poker competitively. A year later, he took down event No. 2, pot-limit Omaha, and pocketed a cool hundred grand.

Maksflaks translated loosely from Norwegian to English as "very lucky." ActionJeff was a homage to "Action Dan" Harrington. Harthgosh was said to be the unfortunate result of trying to say Harsh Goth while intoxicated. The names may not have translated well into modern parlance, but they did translate into a lot of money. All of those people ended up at WCOOP final tables.

Some big names shed their anonymity. Greg Raymer, Chris "Money800" Moneymaker, Tom McEvoy, Evelyn "evybabee" Ng, Isabelle "No Mercy" Mercier, and Wil Wheaton all played publicly in their roles as members of Team PokerStars. Tony "wraptduck" G. outed himself just before he bubbled short of the final table of the main event. Mark "Buster Love" Seif made the final table of the main event and placed ninth. In a performance worthy of his two WSOP final tables, Joe "fidallio" Sebok made a final table, writing later in the official PokerStars blog, "The whole experience was completely thrilling, and I have developed a newfound, healthy respect for the online game. It was full of so much action and enough differences from the felt game to warrant its own strategies and its own excitement."

Robin Hood Radio

With as much money as was on the table, it was going to take something very large to turn anyone's attention away from the WCOOP. Then that very large something happened and put the game in perspective. Hurricane Katrina stormed into the Gulf Coast and destroyed just about everything in its path. The resulting human suffering was worse than anyone would have imagined.

One familiar home in the middle of Biloxi, Mississippi, fell into a pile of shards. Hundreds of miles away in a friend's mountain house in Asheville, North Carolina, the home's owner listened for reports from his family, then turned on his computer and went to work.

"Good evening, everyone, I am the Voice of Poker, Rick Charles."

Charles, like thousands of others, had lost everything in the disaster, and now it was time to work. Charles works for PokerUpdates.com and PokerTalkShow.com. Every night, as the WCOOP reached a final table, Charles signed on and, with a variety of special guests, broadcast around the world.

One night, as the play wound down toward two tables, word began to spread that another big-name pro was in the money and fighting for the final table. It was none other than Barry "crazyplayer" Greenstein.

Greenstein, known for his altruism and charity work, promptly offered to donate any of his winnings to the Hurricane Katrina relief fund. PokerStars backed up Greenstein's offer with a 100 percent match.

Indeed, that was the climate in the middle of the WCOOP. Team PokerStars member Wil Wheaton had organized four charity tournaments on PokerStars and subsequently – with PokerStars matching funds, Greenstein's donation, an anonymous donor, and all the charity tournament buy-ins – raised around $130,000 for the American Red Cross Hurricane Katrina relief efforts.

That night, Greenstein placed 16th in his event, and then he called Rick Charles and spent hours on PokerStars Radio analyzing play at the final table as it moved along. It would prove to be the jumping-off point for a webcast that would grow in popularity around the world, with 10,000 listeners at any given time.

It was just one example of what the World Championship of Online Poker had become. The rest of the examples came in terms of the insane amounts of money the winners of the events eventually won. When that final table of the main event finally finished up at 6:48 in the morning, the top three players had earned more than half a million dollars apiece, and a player by the name of Panella86 held the WCOOP 2005 main event bracelet.

When the WCOOP began four years ago, it was proud to host players from 36 countries. In 2005, players from 82 countries were able to say they had played in one of the biggest poker events of the year without ever leaving their homes

……………..

So, what happened to our friend, the pharmacist, who got into a $1,000 WCOOP event on a freeroll? What was VikingVII supposed to do?

While there may not be a handbook on how to be a modern-day Viking, Guttormsen had read most of the poker books and knew he had but one choice. He had to be ruthless. He had to pillage. And, indeed, he did. In 11 hours and 59 minutes, the unassuming California pharmacist had turned absolutely nothing but effort into $316,638 and a WCOOP bracelet.

Sitting at home when it was over, the old car and brown lawn still in front of the house, the Viking thought he might head for the islands – maybe Hawaii; oh, and play some more poker.

"I want to see if I can count fewer pills and make a comfortable living," he said.

That, friends, is a prescription for WCOOP success.

Features