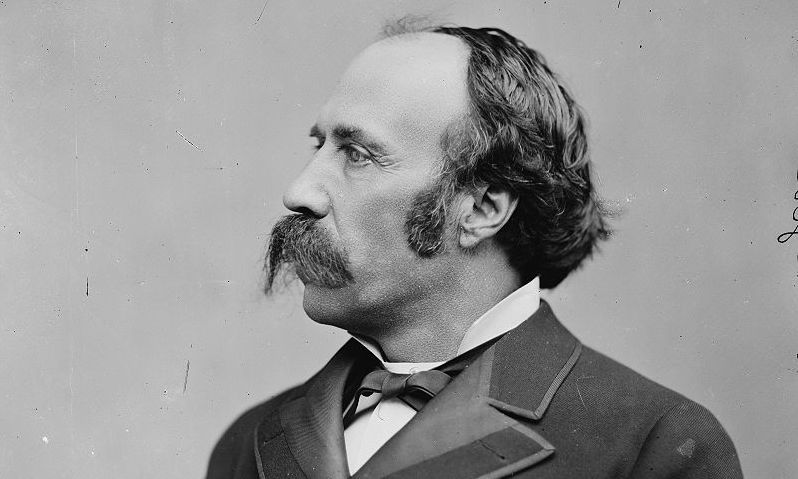

The Time A U.S. Senator Sued Friend After Chasing Poker LossesHorace Austin Warner Tabor Claimed Poker Defeat Was A Loan |

|

|

Sometimes it’s wise not to trust anyone when playing poker for high stakes, even if that person happens to be a U.S. Senator.

That was the case in a poker game back in the early 1880s involving U.S. Senator Horace Austin Warner (“Haw”) Tabor from Colorado and his longtime friend, a man by the name of William H. Bush. This tale was first told in the early 1920s in Connecticut’s Bridgeport Times newspaper.

Senator Tabor, who was also a silver mining pioneer, ended up suing Bush during the early part of his senate stint over what Tabor dubiously claimed was a loan in the poker game. Other debts were part of the suit, but the poker game was front and center. Their friendship eroded “into hatred” when Tabor tried to recover money he had lost to Bush.

A lawyer defending Bush said in a court filing that the senator was actually the big loser in the game. Tabor was said to have made an informal deal with Bush so that Tabor could have the opportunity to win back his money and thus maintain his reputation as a poker player.

Apparently the game was about to break, and Tabor didn’t want to quit down big.

Being viewed as a skilled player back then was sometimes paramount. It apparently was shameful to be thought of as a mark at the card table. It would mean you’re a fish in the political arena too. Playing poker was considered an act of performing “practical statesmanship.”

Tabor was considered to be an expert poker player, so when he was “steadily losing ground” in the game against Bush and it became apparent that his odds of “regaining his position in this game were constantly growing slimmer and beautifully less,” Tabor asked his friend for a favor.

While on the ropes, the senator wanted Bush to continue playing him until he at least got even. Tabor said that he needed to climb out of the hole in order to remain well-respected by the Colorado State Legislature and prevent the “waning of his reputation as a statesman.”

Bush committed to keep playing. Under their under-the-table deal, Tabor would honor his losses, but if Tabor came back in the game, he would fork over half of his winnings to Bush in the form of a rebate.

Bush committed to keep playing. Under their under-the-table deal, Tabor would honor his losses, but if Tabor came back in the game, he would fork over half of his winnings to Bush in the form of a rebate.

That’s how desperate Tabor was.

When the dust settled, the senator had dropped $1,250 to his buddy, which is roughly equivalent to $25,000 today. His hopes for a comeback in the game had failed. Apparently there were either others in the game or people watching on the sidelines, so Tabor wasn’t thrilled when he had to fork over that sum right then and there. It’s safe to assume he knew the political consequences were also steep for being viewed as a deadbeat gambler.

Tabor, apparently fuming as a sore loser, eventually wanted all of his losses back, claiming the $1,250 defeat was a loan. When the other side of the story came out, Tabor decided that Bush’s legal defense (which apparently was simply the truth) was so appalling that he had a court hold Bush’s attorney in contempt. Tabor was also a local newspaper and opera house owner, as well as a prominent philanthropist.

Tabor was able to persuade the Denver Superior Court to fine the attorney, Williard Teller, a sum of $500 for the disparaging legal rebuttal against him.

The case apparently became so controversial that the Colorado Supreme Court was set to take it up. However, before the state’s high court could make a final judgement, the litigation pitting Tabor against Bush was tossed by the lower court.

It was a win for Bush, who argued in court that the senator had tried to freeroll him.

“[Tabor] has not now nor has he ever had any claim at law, equity, good conscience or by the rules of poker against this defendant, and he can recover for said money only on the grounds of ‘heads I win, tails you lose,’ against which all men should protest.”

Tabor went on to become United States Secretary of the Interior in the administration of President Chester Arthur. He later failed in efforts to become governor of Colorado in 1884, 1886 and 1888. Tabor died in 1899 at the age of 68.